In this article, I tell the story of a very visionary CEO who developed an exciting “ambidextrous” concept for a specialist publisher back in the late 90s and “pulled it off”, at least for as long as he worked at the company. Unfortunately, the experiment failed.

The idea

The CEO, let’s call him Michael, had noticed that his product range reached a limited target group, namely experts in various industries. Although the target groups at the time were rather “innovation-resistant”, it was only a question of time. His products were necessary tools, so-called loose-leaf works, kept up to date by monthly update deliveries. It was already clear to the CEO that this business model would not survive the next few years, as technology was developing rapidly and customers were also evolving.

On the one hand, the company had to be as lean as possible with its current business model to be as cost-efficient as possible since the production costs for offline products also had to be recouped. On the other hand, new ideas had to be generated as quickly as possible on how to change the business model to be successful in the long term.

To that end, Michael and his leadership team defined two organisations:

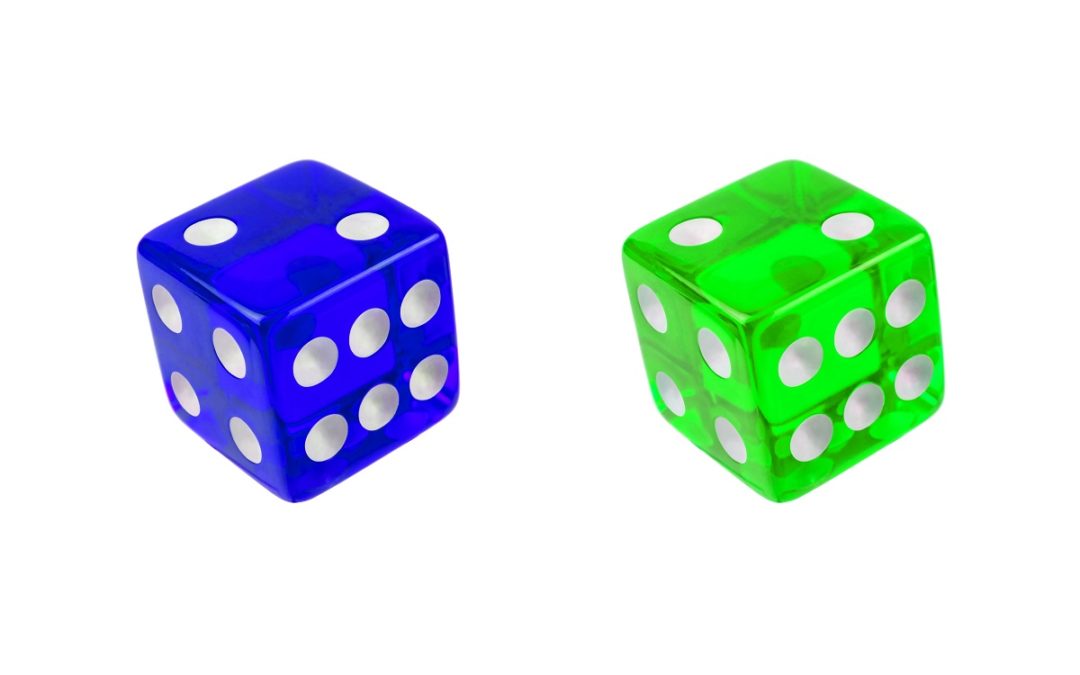

- The so-called “blue” organisation corresponded to the line organisation. Michael introduced a profit centre organisation. Each profit centre was responsible for a specific customer group. Central functions such as administration, marketing, sales and production worked for all other organisational units via an internal allocation model. Here, management was strictly based on key figures.

- The “green” organisation was the new and creative part: There were no executives and employees, but “only” innovators. The members of the green organisation were appointed at the suggestion of the management and the executives.

The only criterion for having an active role in the green organisation was that the person was known as a creative lateral thinker and was interested in working on new issues. This organisation, led by the executive director, was organised into working groups to address specific problems.

The members of the working groups were allowed to work in the green organisation up to a maximum of 50% of their weekly working time, as it was assumed that “blue” projects would result from the ideas born there anyway.

The working groups were led by the person who had the most know-how and energy for a particular topic. Interestingly, only about one-third of the working group leaders in the “green” organisation were also managers in the blue organisation; two-thirds were employees.

The project ideas that emerged in the green organisation were handed over in a prototype stage to the blue organisation – namely to the management of the respective profit centre – to go into implementation there ideally.

The yield

After the idea was presented in a large meeting in which all employees were represented, there was great optimism in the company. Many young employees, especially those interested in technology, expected this green organisation to foster a rapid change in the company.

However, they completely overlooked that the “green” organisation was supposed to be the think tank for the “blue” organisation. The management at that time believed that the executives of the blue organisation would gratefully accept the ideas of the green organisation and ensure a quick, economically exciting implementation of the ideas.

Unfortunately, things turned out differently.

The ideas that emerged in the green organisation – cross-sectoral and in part genuinely visionary, because in some cases there were not yet the IT solutions in the background that these ideas would have needed to be implemented – shattered against the “concrete outer walls” of the blue organisation:

The new ideas that were flushed into the system were viewed critically by the “blue” teams, and many managers – especially those who were not active in the green organisation – became fearful for their standing and power if they took up the green ideas. In addition, the “blue” leaders were often technically overwhelmed with the ideas to be able to judge them well.

The “only” blue colleagues somewhat smiled at employees who worked in the green organisation. When these “green” colleagues presented their ideas, they were usually applauded in a friendly manner and then disappeared into the large circular file in the executive office.

Michael got little of all these experiences of the green employees. Slowly but surely, they saw the blue organisation as a “millstone” and tried to spend more and more time in the green organisation. Michael and his steering team only saw this trend. The attendance was good and so were the ideas.

In the operational meetings of the blue organisation, there were primarily positive figures and very many short-term operational issues, so that for a long time, the green organisation disappeared from the agenda of the regular management meetings.

After about three months came the rude awakening. Michael called a status meeting in the green organisation to find out how the green ideas were received in the blue organisation. The green employees reported in unison that the “pure blue” managers boycotted the innovative ideas practically everywhere, and hardly any project survived an initial meeting. Gradually, the “greens” came out with the fact that they were only regarded as cranks in the blue organisation, and the individual profit centres continued to work just as before. Of the 20 or so green project ideas at the time, not a single one had made it into implementation.

After another six months, which made the situation even worse, the experiment was called off, and restructuring was initiated on the part of the group’s top management, which transformed the organisation from profit centres back into a tightly organised line organisation to save costs. Around 30 % of the employees, especially the “Greens”, left the company – more or less voluntarily.

The learning from this

Ambidextry requires, above all, an attitude from managers that is open to the new without devaluing the existing.

From today’s perspective, I would still regard forming an innovative unit as a visionary idea. Still, the project ideas only have a chance of being implemented if the innovators are also equipped with sufficient “sanctioning power” to implement them.

Recent Comments